Antoine Walker isn't afraid to talk about his personal setbacks with collegiate athletes. He is hoping to prevent them from making the same mistakes.

You were a three-time NBA All-Star, a world champion with the Miami Heat and an NCAA champion with the Kentucky Wildcats. But most of the recent media attention surrounding you has involved your financial issues. Why did you decide to make a documentary, Gone in an Instant, about it?

The documentary shows people, especially young athletes, the trials and tribulations of my life, from earning millions of dollars to filing for bankruptcy. I’ve read a lot of negative things about myself, and I wanted people to see the truth and understand what really happened. We interviewed about 20 people—friends, coaches, family—that have been on this roller coaster with me through my professional life. We wanted to get the truth. I didn’t want to be in the room when the questions were asked. We didn’t give anyone answers to the test. It’s a project that gives other athletes insight on how you can make and lose a lot of money. I think we did a good job of capturing how these things work.

Did any of the answers in the documentary surprise you?

The blame lies with everyone. Everyone rode the train, but when people spoke, it was always about other people. It was never about themselves. The accountability of their role never came out. But, I thought everyone was fairly honest.

What was your background before you became a pro athlete?

My mom’s a single parent. I’m the oldest of six: four boys and two girls. For 19 years of my life, I helped raise my brothers and sisters. My mother changed jobs five or six times and struggled to make ends meet. When I turned pro, the first thing I wanted to do was to put my mom in a situation where she didn’t have to work anymore.

Where did your financial troubles begin?

Once you move your mom to a better situation, and you make sure your immediate family is taken care of, then every athlete lives a different life and can lose track of how much they are spending. They follow different fetishes. I had expensive ones. I had a car fetish, a watch fetish, a clothes fetish. When I was 19 and I turned pro, there wasn’t any kind of manual to help me. As an athlete, we create our own lifestyles. That’s the great thing about my new role as a consultant to Morgan Stanley Global Sports & Entertainment’s financial education program for athletes and entertainers. I get a platform to tell my story to young athletes who are about to start their own journeys. As they embark on their professional careers, the financial education program helps to give them a basic foundation and teaches them how to make smart financial decisions from the start, including how to say no. They get to see real life experiences from someone that’s made a ton of money and made mistakes. I know you want to take care of your family, but you have to hold them accountable. And it’s hard to hold them accountable. It’s hard to say no to your family.

How did you determine who would help you when you turned pro?

I really didn’t know who to talk to. I leaned on my college coach, Rick Pitino, to help me pick out an agent, an advisor. But I didn’t know who to trust. I didn’t know what questions to ask. They don’t teach you these things in college.

When did you know that you were in financial trouble?

It takes a while to figure it out. You’re getting the check on the 1st and 15th, so you’re ignorant to what’s going on with your money, because the money keeps coming in. My biggest mistake was trusting someone to run a real estate business for me. I started this business without having my eyes and ears on him. I trusted someone in real estate that I should never have trusted. I put that responsibility on him to get the job done, and it was totally my fault. I wasn’t even aware there was a problem until 2008. By then, I was home more often, and I started getting stuff in the mail. I began to find out that things that were supposed to be taken care of were being ignored. Pipes were bursting on the property, and things weren’t getting fixed. By the time I got on top of it, it was already basically too late for me to do anything to try to stop it. I’m in a situation where I’m the personal guarantor on these properties, not understanding how powerful that is and how much I’m at risk. These are things I should have understood before I even got started, but I didn’t.

Was that the biggest factor in losing your wealth?

It was a major part of it. Look, there are so many ways an athlete can fall into financial pitfalls. You can spend way more than you should. People can steal from them. Divorce. Bad investments play a big part in it. We can create these great lifestyles, but in one bad investment, or by trusting the wrong person, everything can go bad. That’s why speaking to college kids in the program is so important. When you’re 18, 19, 20 years old, as an athlete, you already have to be thinking about what life will be like when you’re 40. When you’re 50. You want to be able to take care of your kids, and your kids’ kids. This financial education program starts that thought process.

I’ve heard you share your story with many student-athletes around the country. What kind of questions do they ask you the most?

The biggest thing they want to know is what happened to all your friends and family. Are they still around or did they take off? They want to learn how to say no to their parents and family. It all comes down to accountability.

It sounds like in some ways, they are asking you who they should trust.

In a way, they are. What I try to tell them is that you stay close to the people that have been around for the first 20 years, and you try to build. Sometimes you meet new people that can be great for you. But you need to build a foundation that starts with the people you know and avoid people who will put your financial future at risk.

What has been the most difficult part of this journey for you?

The toughest part of the whole thing has been the rebuilding process. You work hard to put yourself in a position where you never have to work again, then you lose your wealth and you have to go to work. And it is work. The saving grace for me has been that I came from a situation where I had very little to start. I know what it’s like not to have wealth. And I survived the tough times, so I know I can do it. But starting over is the hardest part.

Are people willing to help you rebuild or are they constantly reminding you about the past?

You live and learn, and you learn how to block those people out. That’s another thing I try to tell the athletes in the program. The people that don’t have your best interests at heart, you can figure that out really quick if you’re alert. The people that don’t want to help me rebuild, I cut those people off. The biggest part of changing the conversation has been telling my story. I’ve told it enough now, where everyone is beginning to understand the truth and now we can talk about other things as well, like basketball. I’m grateful to Morgan Stanley Global Sports & Entertainment for giving me such a public platform to share my story.

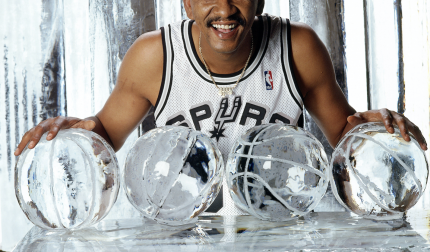

Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images

When you were with the Memphis Grizzlies at the end of your NBA career, did you know that the end of your career was near?

I was a little immature at the end. I had the opportunity in Memphis to be a veteran mentor on the team, but my pride got in the way. I wanted to play. Against my better judgment, I should have accepted the role, but I took a buyout and never saw another NBA uniform again. I thought I was going to get picked up the next day and it never happened. The end was sudden.

You were born a few years too early. It’s a shame we couldn’t see you play in the NBA today.

When I was playing and shooting three-pointers, people criticized me for it. Now, look at Golden State. Having a player like Draymond Green play the stretch-four or the point-forward, they won a championship with it, and the NBA is a copycat league. I need to be about 10 years younger, because they way I played, I could play in the league for 20 years. But more importantly, if I had a financial education program like the one I’m able to speak at now, I probably would have made a lot of different choices in my life. If I can help a lot of other athletes not make the same mistakes I made, I would feel blessed.

W. Drew Hawkins is the Managing Director and Head of Morgan Stanley Global Sports & Entertainment.

Antoine Walker is working with Morgan Stanley and serves as a consultant for the Global Sports & Entertainment Division (GSE). He assists GSE in helping to provide insight to clients, Financial Advisors, and participants in the financial education program based on his first-hand experience with the financial opportunities and challenges encountered by professional athletes. He may also act on behalf of Morgan Stanley to promote Morgan Stanley and GSE to others.

The views expressed herein may not necessarily reflect the views of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. www.sipc.org. Morgan Stanley’s Global Sports & Entertainment Division engaged Athletes Quarterly to feature this profile.

© 2016 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC CRC 1429605 (3/16)