How did you discover basketball?

My older brother Bailey played. I grew up in a poor section of Indianapolis, and there wasn’t much to do. We didn’t have any money. I couldn’t go downtown, because they wouldn’t allow blacks downtown. And they had gangs in certain parts of the city as well. So what do you do? You stay in your neighborhood. You’ve got several good athletes around, and you play sports.

What else did you play?

I played a lot of baseball. That was really the sport of the day. Then I got to meet some of the Harlem Globetrotters at an event when I was 13. Guys like Marques Haynes and Goose Tatum. They were the greatest players in the world to me. I had never seen my brother play a game prior to that. I did see him make a shot that propelled his team into the Indiana State Finals, and it was a big deal because it was the first time that an all-black school made it to the Indiana State Finals. The sad thing about that was that he made the shot, and the coach wouldn’t play him in the finals. Wouldn’t even dress him for the final game.

You followed in Bailey’s footsteps in high school and won two Indiana State Championships with Crispus Attucks High School. As an all black team, I imagine it was a great challenge.

It was difficult. Real difficult. We were an all black school in Indianapolis. The school was built by the Ku Klux Klan you know.

What?

There were a lot of black people in Indianapolis, long before I was ever thought of. And they were going to school because education was a way out of a bad situation. There were really no jobs in corporate America, so a lot of black people went into teaching. So you have these black teachers, black students, what are you going to do with them? The Ku Klux Klan didn’t want them going to white schools, so they built Crispus Attucks. First, it was called Thomas Jefferson, I believe. Most of my teachers had doctorate degrees, but they couldn’t teach in the white schools because of the color of their skin. But you know what, they could still get drafted by the Army. They still had to pay taxes. It was all out of whack.

Is it true that while you were in the Army stationed in the States, you went into a restaurant, and you were refused service because you were black?

Sure they did. I was someplace in Virginia, in uniform, and they wouldn’t serve me.

Did you ever feel during the time that things were changing for the better?

The times were changing, America was changing. Blacks were starting to become part of American sports in a big way. Basketball was changing. A lot of the southern schools were starting to get black athletes. I was the first black to go to the University of Cincinnati. And with that comes a lot of social problems. You couldn’t let a lot of things bother you, because you couldn’t afford to.

Was it culture shock going to the University of Cincinnati?

It was to a certain extent. Nobody told me that in the sports program, there would be five blacks, me and four other football players. No one ever told me that we would be the only blacks at the school. I found out when I got there.

You were the three-time player of the year in college basketball. Then you were selected for the 1960 US Olympic Team. That year, the US had you, Jerry West, Muhammad Ali, Rafer Alston, Wilma Rudolph. What a team!

It was special for me. Not because of all the things growing up. You’re playing for your country. And you’re playing against all the other athletes in the world. And to a certain extent, a lot of the racism and negative feelings are forgotten at that point. You think, they’ll root for me when I get over there.

After college, you signed with the Cincinnati Royals. After a few years, you were able to negotiate what may have been the first no-trade clause and a guaranteed salary.

The reason I got that is because they lawyer for the Cincinnati Royals was from Cincinnati. He wanted me to stay here in Cincinnati and be a Royal for the rest of my life. He actually gave me that clause that gave me the right of first refusal in any trade. At that time, if they didn’t like you, the NBA had ways of getting rid of you.

You were the first basketball player on the cover of Time.

Is that right? Things like that didn’t mean a lot to me. I didn’t think that much of it to be honest.

The story was about how the game is evolving. Basketball was becoming more athletic and less about large, lumbering guys.

Well, it’s just like today. In 1960, a lot of guys came into the league that could move with the ball and run and jump. Fortunately for me, I played forward in college, but I was a guard in high school. The reason why I played forward in college was because the coach had a rebounding drill, and I was getting all the rebounds. So he said, “You’re a forward.” They said I was big, 6-foot-5, 210 pounds. But there were a lot of guys bigger than me: Tom Gola, Richie Guerin. Jerry West and I were about the same size. But I could handle the ball. I could maneuver.

People don’t realize how athletic some of the great players of the 1960s were. You were a track and field athlete. Wilt Chamberlain was a sprinter and a high jumper. Do you feel like that has been distorted over time?

I wasn’t an Olympic level track athlete, but I did the high jump and the broad jump and the hurdles. It was a lot of fun. Where I grew up, athletes went from sport to sport—track, baseball, football, basketball.

Was it exciting for you that the game was evolving athletically?

In high school, you would see so many great athletes in the parks. You get the sense that you can try different things and be successful. I played off of people. Basketball is a game of action and reaction, which is what I did.

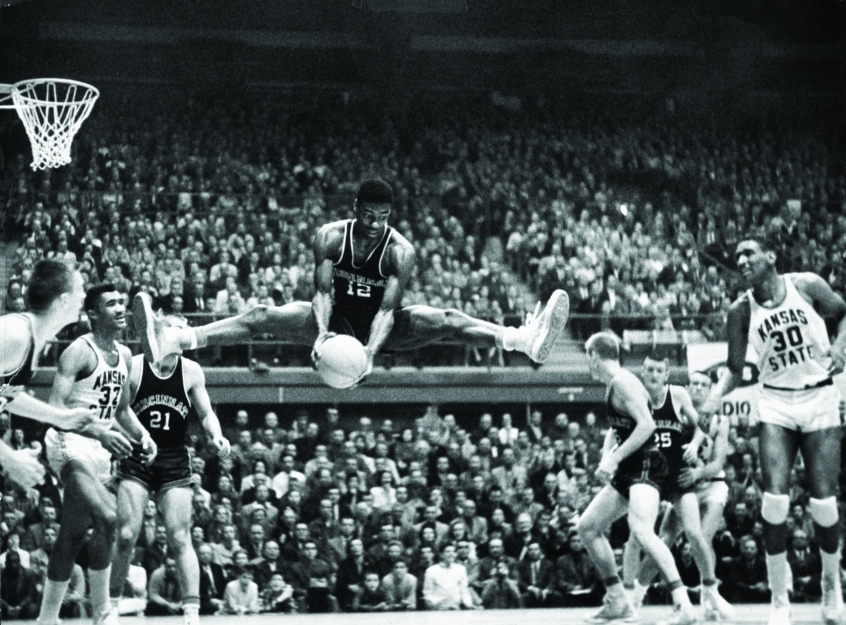

James Drake/Getty Images

In 1963, you lead the Royals to victory in a playoff series against the Syracuse Nationals. Then you take a 2-1 game lead against the defending champion Boston Celtics. And then…?

(Laughs) The Royals management didn’t have any confidence in us. So that week, they had booked the circus in our arena. The circus! So we played in a small gym at Xavier University. The Celtics beat us in the seventh game of the series. But we didn’t have the team to play against the Celtics. They had a lot of great players.

How does a team like those Celtics compare to today?

A lot of people today don’t understand basketball. Why is Golden State winning? Golden State is winning because these guys can put the ball on the floor and go somewhere with it! There are a lot of guys who can shoot the ball! But what big people can put the ball on the floor and do something with it? What are big guys supposed to do, just lumber in there and stand and hope you can get a dunk? That’s no good! Teams today, they don’t have multiple guys. You need two or three MVP candidates to win games today, because all it is is a one-on-one game. Set a high pick, and boom. There’s nothing else.

Why do you think the game has evolved this way?

Even in college, coaches want you to shoot three pointers or get inside and dunk it. They want you to power the ball in. Well, if you got a good defense, how are they going to power the ball in? Then they wonder why they get beat all the time. You got guys that can’t dribble. They don’t understand what the offense is trying to do to them. When certain things happen, you know that other things are going to happen. They don’t understand that at all. They run the same dull plays all the time. You need movement.

Speaking of movements, how did you decide to get involved with the NBA Players Association?

My teammate, [Hall of Famer] Jack Twyman asked me to get involved. I respected Jack so much that when he asked me, I agreed to give it a try.

Your leadership helped convince the players to nearly boycott the 1964 All-Star Game. Can you tell us what happened that night?

1964 was the first year that the All-Star Game was going to be televised. Larry Fleisher, our executive director, had met with J. Walter Kennedy, the NBA commissioner at the time, and Fleisher got an understanding that he would be able to represent us in meetings. Before the game, we got word that the owners had rescinded their decision to allow Larry to represent us. So we got both teams into one locker room, and told them what was going on. We had no representation with the owners, and I said I didn’t think we should play the game. There was a lot of tension in that locker room. A lot of guys will tell you now that they were all behind it, but that’s not quite true. Some guys felt we should play. The money was important to them, and they were afraid that if they didn’t play, they were going to get cut from their team.

Here’s the thing that’s amazing to me. You have that very tense All-Star game showdown in 1964. At that time, your wife was due with your second daughter. And you go out and win the MVP of the All-Star Game! Despite everything that’s going on—labor unrest, civil unrest—you were still expected to play at an elite level at all times.

The toughest thing out of all that time was when my wife went down to Selma, Alabama the following year to march with Dr. King. My teammate, Wayne Embry’s wife was going to Selma. Wayne’s wife was good friends with my wife, Yvonne. So Wayne tells me, “Your wife wants you to call her.” So I call, and she tells me she’s going to Selma to march with Dr. King, and I say, “Are you crazy? What are you going to do about the kids?” Here we are about to play a game, and they’re about to get on a bus to go march. It was really courageous of her. I don’t know if she understood at the time the danger that was involved in it.

In your book, you say that the civil rights leaders of the time would never ask a famous athlete to speak out and risk their careers.

That’s absolutely true.

I know you’ve said that you were able to challenge some things because of your ability as an athlete; you felt it was harder for them to cut you. But truth be told, you didn’t have to challenge any of it. Yet you did.

I don’t know, I guess so. I look back on it now…

I know you’re being humble, but some of the things you took stands on affect a lot of athletes, even today.

None of the other guys were doing it. I was new in the league, and there were stars there before me, and there were a lot of white stars. But there weren’t a lot of guys standing up. I wonder about that now.

Even at the All-Star game. These were the best players in the world. Was it possible that they would have been cut?

Well what we did was to say, “OK, lets get the best players we can to be player reps, so that this way, they can’t get rid of you.” We had to do that. If I hadn’t been a good player, I would have been gone.

At the end of that season, you were only the second guard ever to win the MVP. And this was when both Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain were at the peak of their careers.

At that time, it was really difficult for anyone other than a center to win the award. It was believed that if you had a good center, you could win the championship. It’s not that I averaged 10 points, 10 assists and 10 rebounds. I was averaging 31 points, with 11 assists and 10 rebounds. Now, people win MVP’s now when the press gets behind them. Stephen Curry played very well last year. His team did well and won the championship and he won. It wasn’t like that back then. Jerry West never won an MVP award. Can you believe that?

Let’s talk about some of the playing conditions. How many preseason games would you play a year?

I’d say 15. Maybe more. We didn’t get paid for any of them.

You play about a third of the season at home, a third of the season on the road, and a third of the season…

In Podunk. Small markets all over the place. We’d get on the bus and travel somewhere else to play. We’d play almost every night. When we flew, we had to take the first flight out in the morning, sometimes 6 a.m. We’d fly commercial coach with stopovers. I don’t think guys would do that now.

In these smaller towns where you are essential barnstorming, but all the games count, are you still facing discrimination?

All the time. Even in college, when we would go on the road. I tried to go to the movies in North Texas. They said, “Why don’t you sit upstairs?” I said, “No, that’s not for me.” In the NBA, we were in Lubbock, Texas at the Holiday Inn at noon, and there’s nobody in this place at noon. They pull this big curtain around us. I said to Wayne Embry, “Wayne, I’m not playing tonight.” He said, “Why?” I said, “Because of this curtain.” So I went and told the manager. They took the curtain down.

Were there other incidents like that?

They happened all the time. I mean, I wasn’t the only one who suffered through some of these things. When you were black, they would put an asterisk next to your name in the hotel book. Hell, I know who the white guys on the team are! I don’t need to room with them. It didn’t matter to me. I roomed with Bob Boozer. The Celtics had four black guys. Most teams had one or two black players, but they didn’t get to four or five.

What was your first impression when the ABA launched in some of these smaller markets?

At first, it was like a sideshow. They had the red, white and blue ball. A lot of guys were playing in it, because they couldn’t make it into the NBA. The Indiana Pacers wanted to sign me but they offered less money than I was making. But eventually, they got much much better. We played several All-Star games against them and we won, but they started to get better talent. It was still going to be hard for them to get stars to play in some of the markets and arenas they had at the time. It was part of the reason why the Oscar Robertson case became so important.

How did the Oscar Robertson antitrust suit come about?

The suit was about playing conditions and the right of first refusal. We didn’t care for the leagues to merge, because that would eliminate another source of revenue for players. We wanted to get better playing conditions and travel. But the real thing was the right of first refusal. Before that, if an owner had you under contract, and he didn’t like you, he could keep you from playing anywhere else. And nothing was said about it. We met with several owners. Some owners were nice about it, but some definitely wanted it their own way. Players needed to have a say in where they were going to play.

In Cincinnati, when Bob Cousy became the coach, didn’t he try to trade you?

He sure did. He was hired by a group from Buffalo that wanted to move the team to a 17,000 seat arena in Kansas City. Here I am in Cincinnati, I was the college player of the year for three years in a row. In the NBA, I was All-NBA for 10 years in a row. Never caused any trouble. Married to the same woman for years. And then the team is saying that I never did anything! Then the papers get involved! The Cincinnati Enquirer and other papers are running stories that I’m goldbricking, and I’m not trying hard because Cousy is coaching the team. The only thing I knew about Bob Cousy was that he played. I never socialized with him. I couldn’t believe the writers and what they would say. I wasn’t going around to the writers telling them anything. They were just watching me play on the court. And even then, they were trying to tear down everything I did. They even wanted to take that away.

Didn’t the ownership award the team MVP one year to Johnny Green?

They did! And nothing against Johnny, but here I am, All-NBA for the 10th year in a row, and they still had to do that. That’s the kind of times we lived in. There are some things in life you never forget. And you probably should forget. But there are some things I will not forget. After 10 years, to tell me I hadn’t done anything? And for the press to run it as though they were right? I’ll never forget that.

What did the Royals do?

They tried to trade me to Baltimore. They just wanted to get rid of me. They were going to get back Gus Johnson and someone else. Well Gus Johnson’s leg was all messed up; he couldn’t even play anymore, but they just wanted to get rid of me. The Lakers said they had Jerry West already. The Knicks said that they had Walt Frazier and didn’t want to cause any problems. I couldn’t understand that. Guards are guards! So I decided to go to Milwaukee and play there.

The thought of you pairing up with West or Frazier is mind boggling. But you go to Milwaukee to team up with Kareem and you win a championship.

We could have won 73 or 74 games that year. Our coach, Larry Costello decided to rest everyone at the end of the year.

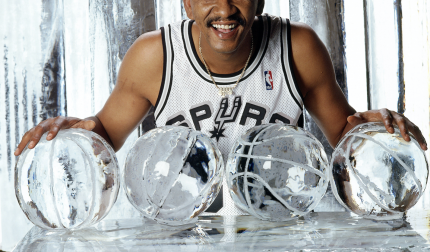

Focus on Sport/Getty Images

In 1973, Sport Magazine runs a cover story on you. On the cover, your image is disappearing, and the story is called, “How much is left of the Big O?”

You have to realize in those days, black players were always at the center of criticism from writers. The guy that wrote the story, I don’t know why he would say it. I was playing 41 minutes a game at the time. Then, the Bucks had something they called an “Appreciation Day,” but I knew it was a retirement day. The last year I was with the Bucks in 1974, my contract expired at the end of the regular season. I was playing in the playoffs without a contract. And they didn’t even know it! I could have said I wasn’t going to play, but I wasn’t going to do that to my teammates. There were guys in the league older than me. They weren’t writing about how much they had left. Look, if you don’t feel I can play anymore, just say so. Don’t sign me. But don’t plant stories about how much I have left.

That last season, you went to the Finals.

We went to Game 7. We should have won. [Coach] Larry Costello kept putting forwards in to play with me in the backcourt. It didn’t work at all. And you couldn’t convince him not to do it. He was hardheaded about it all. Red Auerbach was really smart. After that game, he started doing interviews wondering, “Can Oscar play any more?” He didn’t want me playing against his teams.

The Bucks had two of the greatest players of all time in you and Kareem, and within a year you were both gone.

They haven’t won since.

Were you tempted to come back? I mean, you lost in the seventh game of the Finals! To come that close, did the competitive fire in you want to give it one more run?I was going to leave. They didn’t know it. When they did the Appreciation Day, I told my wife, that was it. I was done. 14 years was enough for me.

You also had broadcasting opportunities. You started broadcasting national TV games.

That was a joke. I should have known after the suit, the NBA owners were never going to want me to be there. There was no doubt in my mind that I was blackballed from basketball.

You were blackballed because of the antitrust suit you filed against the NBA?

I was doing games on television as an analyst, and I saw in a deposition that they didn’t want me there. They said, “Why do you have Oscar Robertson? You know he’s against what we do.” So I knew I was gone.

When the suit was settled in 1976, did you feel vindicated?

I had been out of the league for a few years, but I stayed close to the situation. I didn’t realize the star-studded platform it would put players on. The Oscar Robertson case made superheroes out of NBA players. They started making millions of dollars. They were on national TV all of the time. They got Nike contracts. Can you imagine a guy getting a $300 million contract to wear your shoe? This is where we are today. If it weren’t for the Oscar Robertson case, we never would have gotten here.

When you retired, you were second all-time in points behind Wilt Chamberlain, first all-time in assists and 16th all-time in rebounding. I don’t think we’ll ever see a player that high on all of those lists again.

When you see stats now, my name still comes up. But some names are starting to get left out. You never hear Elgin Baylor’s name mentioned anymore. Why is that?

Kent Smith/Getty Images

What advice would you give the player’s union today?

I would say that the players’ likenesses can no longer be part of collective bargaining. There was a deal cut some years ago that hurt the Players Association forever. Larry Fleisher sold the players’ image rights to the league for $500,000 a year. Then the league ran it up to a $3 billion business. We could have done that ourselves! The players could be making the money the NBA is making, rather than whatever the percentage is that they give the players. And we never voted on making that deal. Guys are making so much now, maybe it doesn’t matter to them anymore. But it’s an international game now. Those rights are worth a lot of money.

Did you ever dream that the NBA would be what it is today, when you entered it in 1960?

Not at all. The lawsuit changed some things. And I wasn’t the only guy that faced obstacles during that era. I think it has become more important for players to say what people don’t want them to say. Sometimes players don’t want to make a comment. They're afraid their comments are going to hurt them. If they’re a great player, nothing’s going to happen to them. There’s too much money in the game now. If a guy can’t play, maybe they’ll get rid of him. But if he’s a star, he’s going to play. I’m not saying that a player should say something crazy or jeopardize his family’s well being. But some times, you have to be able to stand up and say, “This is wrong.”