On the night of October 15th, 2014, Emanuel Augustus called his fiancée, Dorothy Anthony, from the North 14th Street Park boxing gym in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Anthony was surprised because Augustus didn’t own a phone. Never has throughout his “Have Gloves, Will Travel” boxing career. At age 39, after a three-year hiatus from the ring and with a pro record of 38-34-6 and a staggering 614 professional rounds to his name, Augustus was planning to return to prizefighting.

Throughout his 18-year pro career, Augustus had been an entertaining fan favorite in the boxing world. Known as “The Drunken Master,” he was a regular on ESPN’s Friday Night Fights, appearing on the program 11 times. His 2001 knock ‘em, sock ‘em fight with Micky Ward was voted by the network’s viewers as the Fight of the Decade. Floyd Mayweather—one of boxing’s all-time greats who has been in the ring with champions such as Oscar De La Hoya, Shane Moseley, Miguel Cotto and Manny Pacquiao—still refers to Augustus as the toughest fighter he’s ever faced.

After spending several years fighting out of Brownsville, Texas, and two more in Australia, Augustus returned home to Baton Rouge in 2012. He reunited with Dorothy Anthony, a woman he had known for almost twenty years. And he was already beginning to show the signs of an aging fighter. His short-term memory was beginning to fail him.

“Baby, I’m in the gym, and I’m fighting for us.”’ Augustus told Anthony, who is known to her friends as Dot.

“Did you train today?” she asked.

“No, I was just helping some guys out,” Augustus said. “But I’m going to get back in the ring. I’m going to fight again, for you and me.”

Dot didn’t want to see him return to the ring professionally. But for the moment, she was glad he was happy. After expressing their love for one another, Dot asked Augustus if he would pray with her on the phone before he hung up. A deeply religious person, she wanted to share a divine moment with him. It was colder than usual that fall evening, and Augustus was planning to sleep on the street.

Since he had been back in Baton Rouge, Augustus had been homeless at various times during his stay. Occasionally he would stay in a shelter. An argument with a police officer landed him in jail overnight once before, until Dot came in to straighten everything out. After that, he began avoiding the shelters.

Dot had been living with her parents—she worked for the cleaning service they owned—so she couldn’t take Augustus in. And being as prideful as he was, Augustus didn’t want to be a burden to anyone, including several of his closest friends who would have gladly let him sleep on their couch that evening.

“Baby, it’s cold. You need to sleep inside tonight,” Anthony insisted.

“I will, baby,” he told her.

Augustus decided to head to a cousin’s house within walking distance of the gym to spend the night. He packed his workout clothes into a plastic Walmart shopping bag, tied his gloves together and threw them over his shoulder. Then he headed out into the darkness.

Nearly five blocks from the gym, two men began to argue in a red sports car while driving down nearby Louisiana Avenue. According to police, the argument between the two cousins in the car became so intense, the driver slammed on the brakes to stop the car. The passenger, a 21-year-old named Christopher Stills, allegedly jumped out and fired his gun several times over the top of the car. One of those bullets found its way to the back of Emanuel Augustus’ head.

A boxer always knows that the shot that hurts the most is the one you never see. Upon entering Augustus’s head, the bullet split. A portion of it cracked a vertebrae in his neck. Another fragment nicked an artery.

After falling face down on the pavement, Augustus slowly pulled himself back up to his feet, feeling his neck, trying to understand what had happened before collapsing again. He was rushed to the hospital, as the damage caused by the bullet began wreaking havoc on his body.

By the time Augustus made it to Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center, he was in critical condition. Doctors had to induce a coma to reduce the swelling in his brain. During the nearly two weeks in the coma, his friends and family thought his brain may no longer function again, even if he did survive.

Day and night, Dot prayed by his bedside, often sleeping in the hospital lobby when she wasn’t allowed to be in his room. Several news outlets prematurely reported that Augustus had died. It would be months before they knew Augustus would survive, let alone be able utter a single word or take a step. But it wasn’t the first time that people counted out The Drunken Master.

In the fight game, there are two kinds of fighters—the A-side and the B-side. When you’re an A-sider, you are the golden goose, and everything will be done to protect you, so that you may continue to lay expensive eggs that will make everyone around you rich. Matches are made for you against favorable opponents to protect your record and earning power. Often times, the fights are made in your hometown, in front of an adoring crowd, and with judges that will score the fight generously. You get to pick the weight of the gloves, the size of the ring, and the lion’s share of the purse. Life is good for the A-sider. Unfortunately for Emanuel Augustus, he was born on the B-side.

And if there were ever to be a B-side Hall of Fame, Augustus would be its first inductee through unanimous voting. Though he hasn’t fought in over four years, his name is mentioned with reverence by fight fans, because no matter how much the game was rigged against him, he always gave them their money’s worth. When the final episode of ESPN’s Friday Night Fights aired earlier this year, ESPN play-by-play man Joe Tessitore chose Augustus’ clash with Micky Ward as his favorite fight in the program’s 17-year history, a bout that he didn’t even work. He watched it at home, as a fan.

It didn’t matter if there was two months, two weeks or two days notice, if a top fighter needed an opponent at 135 pounds (or 140, or sometimes more), Augustus was ready to invade the A-sider’s home turf and put on a performance that would leave the crowd standing and applauding.

“You have to understand how the fight game works,” says LJ Morvant, one of Augustus’ closest friends in Baton Rouge for over 20 years and a constant presence in the 14th Street Gym with him. “There were lots of times when promoters knew they wanted Emanuel to fight. And they would give him a week’s notice so he couldn’t train properly. There’s walking around shape, there’s training shape and there’s fight shape. Emanuel almost never had a chance to walk into the ring against a good fighter in fight shape in his life.”

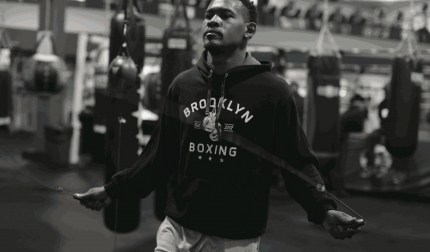

Emanuel Augustus with longtime friend, LJ Morvant

Augustus, we believe, was born Emanuel Burton on January 2, 1975. As with many things in Augustus’ life, the facts can be as elusive as he was in the ring. He does not have a birth certificate or drivers license to verify this information.

During his career, he took the name Augustus from the man who married the woman he believed to be his biological mother. Throughout his childhood and teenage years, he grew up in the foster care system, moving from home to home, until he was 17 years of age. That’s when he came the 14th Street gym under the tutelage of trainer Frank James.

“Emanuel was always ready to take a fight, because he sparred every day,” says another long time friend and sparring partner, James ‘GT’ Georgetown. Georgetown. Now a matchmaker for boxing and MMA cards in Baton Rouge, Georgetown once fought as a 154-pound super welterweight out of the 14th St. Gym.

“We would be going at it,” Georgetown says, “then after the bell, he would try to get a few more shots in. So I’d hit him back. Then he’d keep fighting. Then the bell didn’t matter no more.”

“GT isn’t doing it justice,” Morvant says. “When these guys would spar, everything in the gym would stop. People would put their elbows on the ring apron and watch. And it was always, ‘One more round! One more round!’ They’d go fifteen rounds before Frank had to chase them out of there. And that was it for the day. No bag work, no jump rope, just sparring. I don’t think people realize how great of an athlete Emanuel was in his prime. GT, do you remember when we would go running?”

“Shiiiiit!” Georgetown says laughing.

“Frank James would make all of us run two laps around the lake here in Baton Rouge,” Morvant says. “We would be jogging. But Emanuel would be running. He would lap us around the lake. By the time we finished two laps, he had already finished a third.”

James "GT" Georgetown sparred with Emanuel in his earliest days as a pro fighter in Baton Rouge.

Throughout his pro career, Augustus traveled around the world with a pair of gloves over his shoulder, ready to take on anyone who challenged him. Despite all of his experience, he never watched a single second of film or video on any opponent he faced. Russia, Germany, Denmark—did it matter where his opponent was. In another guy’s hometown, judges weren’t going to give you a fair shake anyway. Especially when your opponent is maintaining an undefeated record that’s good for the promoter’s business.

Early in his career, Augustus was 8-4-1, with all four losses coming in his only four fights at the time in Texas, a state notorious for controversial decisions that favored hometown fighters. “Even with those losses, Emanuel was still seen as a talented guy,” Morvant says. “Early in his career, they threw him into a 10-round fight with a guy named Pete Taliaferro. Taliaferro was 31-5, and he fought him in his hometown of Mobile, Alabama. Emanuel fought well enough to win some of those fights in Texas, but that was the first big fight that he had where most of the crowd thought that Emanuel had won the fight.”

In September of 1998, Augustus flew to Denmark on three days notice to fight their 38-1 contender Soren Sondergaard. Augustus floored Sondergaard twice in an eight-round fight. He was awarded a draw for his efforts. Twelve days later, he beat Eduardo Martinez in New Orleans with a sixth-round KO. Another 10 days after that, he flew to England to beat Jon Thaxton. While most fighters require 12 weeks of training camp to prepare, Augustus fought three professional fighters in three different countries in a span of three weeks.

It was that fighting spirit that made Augustus a crowd favorite throughout his whole career. Augustus last fought in January of 2011. Fighting a 23-0 Kronk Gym prospect named Vernon Paris at the Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan, Augustus looked like an old fighter, taking several blows to an already damaged left eye. Then, seeing his opponent was out of gas in the fifth round, Augustus stepped on the pedal with furious combinations. When the ring announcer revealed that Paris had won, with the help of two innocuous point deductions for Augustus by the referee, boos rained down from the Silverdome crowd for their hometown fighter.

Augustus dropped out of sight after his last fight in 2011. Even if a promoter did want him to fight, they most likely didn’t even know how to contact him. He had returned to Baton Rouge where his closest friends implored him not to fight anymore. They could see that Augustus hadn’t quite been the same person after coming back from Australia. But Emanuel always did things his own way. Then the night of the shooting changed his life forever.

Emanuel Augustus lives in the last house on a dead end street in Baton Rouge, just a few yards from the Mississippi River. About 60 feet away from his apartment, freight trains run along the tracks, day and night.

To say the building that hosts his apartment is modest is being modest. Four apartments combine to form a structure the size of a one-family home. Nearly two months ago, Dot moved out of her parents’ house to the apartment and had Augustus move in with her. His friends even hung an Everlast heavy bag on the front porch to inspire him to get out of the house and move around a bit.

I meet LJ Morvant outside Augustus’ apartment. Morvant has offered to be my tour guide with Augustus. He prepares me that Augustus is no longer the guy I once knew from television. Even before the shooting, his years in Australia took a toll.

“He went there to spar with Kostya Tszyu, a Hall of Fame junior welterweight,” Morvant says. “You know about all of his Emanuel’s fights, but he constantly sparred with the best fighters in the world. While he was in Australia, the promoters suckered him in with a few easy fights at 147 pounds.” (Augustus primarily fought at either 135 or 140 pounds.)

“After a few wins,” Morvant says, “Emanuel thought to himself, ‘This must be my new weight class.’ Then they put him in with Wale Omatoso. That night, Omatoso looked huge. When Omatoso rehydrated, I can’t say for sure, but he looked like he was close to 170 pounds. He looked like a beast, and Emanuel took a beating. He had some problems with his left eye after that. I think he also had a concussion. And this was a guy who had the best chin I’ve ever seen. But Emanuel being Emanuel, he went right back into the gym after it was over, concussion and all.”

Morvant brings Augustus out of the apartment. Augustus looks a bit frightened at first. I would soon understand that it’s hard for him to see me, or anyone, unless he is within a few feet away. The Drunken Master dreads are long gone. His hair is cut very short. His left eye is half closed, and the left side of his mouth is permanently raised because of nerve damage. After the shooting, because of a constant ringing in his right ear, he speaks at a high volume in a slurred tone.

Morvant explains to Augustus who we are.

“Well why are you here?” Augustus asks.

“We’re here because so many people want to know how you are doing.” I say. “Do you know how much boxing fans loved watching you fight?”

“For real?” Augustus asks. “You’re bullshitting me.”

“It’s true,” I say. “All those entertaining fights: Floyd Mayweather. Micky Ward. People still remember those.”

“For real?” Augustus says again. “Wow!”

I ask Augustus if he hits the bag frequently.

“No, not at all,” he says. “My balance isn’t too good. And I have double vision in one of my eyes. It’s hard to hit two bags,” he says laughing.

As Augustus begins to become comfortable with us, his sense of humor starts to show itself. He is entertaining, even self-deprecating. It feels like we are in the presence of The Drunken Master again. He begins to hit the bag for us. First slowly, then picking up speed and combinations, occasionally pausing to recalibrate and balance his feet. Though he hasn’t hit the bag for a few weeks, he hits it without gloves for several minutes, at top power, in the 90 degree Baton Rouge heat and humidity.

“What do you think?” he asks.

“You still got it,” I say.

“Do you know why I sound like a handicapped person?” he asks.

“No, why?”

“Because, I am one. (laughs) Would you like to come inside?”

Augustus unlocks the door to the house and brings us in.

“Welcome to my humble commode!” Augustus says. “Do you get it? It’s a shithole!”

The apartment is even smaller than I imagined from the outside. The living room/kitchen area contains a television and video game system. There are no chairs to sit on. Through the doorway past the stove, which is about 12 feet from the front door, is a small bedroom that contains a simple air mattress on the floor.

“You have to understand,” Morvant says, “This has always been the way that Emanuel has lived. I remember going to visit him at another place in a really rough part of town. I mean, you could see people walking around with guns in their waistbands. And when I went into Emanuel’s place, it was the same set up—air mattress, TV, video games. I think it was Nintendo at the time. And he was perfectly comfortable there. He was always just a big kid. If he had his video games and a big bowl of cereal and some weed—he loved his weed—he didn’t need anything else. And this was when he was fighting big fights on ESPN.”

“So what did he do with the money he was making?” I ask.

“He would, literally, have cash in his hands,” Morvant says, “and he would ask people, ‘How much do you need?’ It made him feel good that he could make other people happy. It wasn’t good for him at all, but that was Emanuel. He always did things his way.”

I ask Emanuel if he would take us to the 14th Street Gym.

“Why?” he says. “I don’t go there anymore. There’s nothing there for me.”

“He hasn’t been there since the shooting,” Morvant whispers to me.

“See the guy there now at 14th Street, the trainer, he’s religious,” Augustus says. “I’m not down with that. Let me ask you something. Why would God let what happened to me happen? Right? If there was a God, why would he do that to me? It don’t make sense.”

“Maybe he knew you were the only guy who would get up,” I say.

“Maybe he has another purpose for you,” Morvant adds.

Augustus points at Morvant. “If he has a higher purpose for me, I can live with that,” he says. “But if he did it just to see me get up? That’s some bullshit right there.”

Nevertheless, perhaps because it will make me happy, Augustus agrees to come to the gym with us. As we enter the facility, it looks more like a fitness center with a ring than a laboratory for legendary sparring sessions. There is not a single poster or photo on the wall of any of the fighters who have been there before. It’s as if the history of the gym had been covered with a fresh coat of paint. A young man and woman are taking a boxing fitness class in the ring when we arrive.

Augustus is welcomed by one of the trainers there. He says hello to the boxing students and apologizes for interrupting their class. To them, it appears that a disabled man has wandered in off the street. They have no idea that this is the man that fought Floyd Mayweather, Micky Ward, and John John Molina. The man that would make boxers stop their workouts every time he entered this very ring, just so they could watch and learn. But it’s their time now.

To them, it appears that a disabled man has wandered in off the street. They have no idea that this is the man that fought Floyd Mayweather, Micky Ward, and John John Molina. The man that would make boxers stop their workouts every time he entered this very ring, just so they could watch and learn. But it’s their time now.

Augustus sits beneath the speed bag rack as we take photos, while Morvant fills me in on some of Augustus’ legendary sparring sessions that took place between these walls.

“It may sound like a cliché or an exaggeration,” Morvant says, “but during sparring, Emanuel was always the last guy to leave the ring. He’d be done with one guy, then he’d call out another guy. Didn’t matter what weight class they were in. They could be heavyweights. He was 135 pounds! He’d get them in the ring and light ‘em up until they were done! He would, literally, keep fighting until there was no one left to fight in the gym. And you just couldn’t hit him. When I sparred against him, there were times where he wouldn’t throw a punch, and I would just get tired from trying to hit him and missing.”

“This is where The Drunken Master was born,” Morvant adds. “All the stuff you saw in the ring, the showboating, he did it here. He would fight with his hands behind his back and do all the dancing. There was always music playing at the gym, so he was always dancing in the ring. It’s just that in the actual fights, when he was dancing, the music was inside his head.”

You have to watch The Drunken Master style to understand the effect it had in the ring. It was so unorthodox and unique, it paralyzed fighters, hypnotized by its bizarre sequence. At some point in the middle rounds of a fight, when Augustus was confident that he could not be beat, he would begin to dance in the ring, much to the consternation of the referee, his opponent and the announcers at ringside—everyone, that is, except the fans.

It would begin with a shoulder shimmy by Augustus. He would then start to sway onto his right foot, swinging his left glove low across his body. Then he would sway onto his left foot and swing his right glove low and across. He would repeat it a few times just to ensure that his opponent realized it was not an accidental dance step to regain his balance.

As an opponent would begin to try to engage, Augustus might kick his feet toward the fighter like an improvised Ali shuffle, but only with his upper body improbably bent backwards, like a cartoon character. If a fighter refused to engage, and they often would, Augustus would sometimes put both gloves behind his back and sway back and forth in front of his opponent with his face thrust forward, daring his opponent to try to hit him, almost as if he were casually ice skating in the park.

“It was the media that started with all The Drunken Master bullshit,” Augustus says as we sit for dinner at TJ Ribs, a local barbecue favorite in Baton Rouge. “That wasn’t me. I never called myself that. I just wanted to entertain people. If you were watching me fight, I wanted to give you your money’s worth.”

“Do you know where a lot of these moves came from?” Morvant asks. “They came from the video game Tekken.”

“Really?” Augustus asks, seeming a bit confused.

“Absolutely, buddy.” Morvant says. “Emanuel would play it night and day when he wasn’t in the gym. He would borrow some of these capoeira moves. Emanuel, do you remember Steve Fox?”

“Steve Fox!” Augustus says. It’s the most animated he’s been all night. “Did you play Tekken?” he asks me. “There was this character named Steve Fox. He had this punching combination. Do you want to see it?”

Augustus looks around the crowded restaurant. He suddenly becomes self aware of his surroundings.

“Maybe it’s not a good idea to do it here,” he says. He takes one more look around. With no one behind him, he says, “Here, let me show you.”

Bracing himself by placing his right hand on the table, he pushes himself up from the chair slowly. He gets into a fighting stance. Then, the punches are lightning fast. “Bam! Bam! Bam! Bam! Bam!” Augustus shouts. The twelve-punch combination is etched in his mind and muscle memory.

“Did you see it?” he asks. “Do you want me to show you again?”

Dinner arrives as the waitress delivers a rack of ribs and baked potatoes for each of us.

“What’s this?” Augustus asks.

“They’re barbecue ribs,” Morvant says. “You’ll like them! Give it a try.”

Augustus shakes his head from side to side. “It’s too much food! I’m good with the potato and my Sprite. Can I get more Sprite?”

“Of course,” Morvant says. “Would you rather have a hamburger?”

“No,” Augustus says. “I’m fine. This doesn’t make sense. How do you eat these things?”

We begin to talk about what happened after Augustus was shot. How he spent several weeks in a coma. Morvant explains that when Augustus came out of the coma, the nurses made a board with photos for him so he would know where he was. His short-term memory, which was showing small signs of difficulty before the shooting, had worsened.

“They didn’t do that!” Augustus shouts. “I don’t remember that!”

“They did,” Morvant says. “Do you remember doing physical therapy in New Orleans?”

Morvant explains how after he left the hospital in Baton Rouge, Augustus was transferred to a facility in New Orleans where therapists worked to help him begin walking and talking again.

“For the first six weeks, he couldn’t eat anything,” Morvant says. “He still has the feeding tube in his chest. For those six weeks, it was nothing but Ensure in a bag. The therapists had to teach him how to swallow again.”

“No they didn’t!” Augustus says, a bit more agitated. “I was never in New Orleans!”

“Yes, you were buddy,” Morvant says. “It’s OK if you don’t remember. You’re not supposed to remember. You were getting better.”

“It don’t make sense!” Augustus says.

Teary eyed, he gets up and staggers slowly away from the table.

“Should we take him home?” I ask. “Maybe this is all too much.”

“Let’s give him a minute,” Morvant says gently. In a few minutes, Morvant goes outside and speaks to Augustus alone. Soon, they come back to the table together.

“I’m sorry about that,” Augustus says. “Sometimes, I get frustrated.”

“It’s OK, buddy,” Morvant gently says, bringing his face closer to Augustus.

“Can you see me now?” he says, teasing Augustus.

Augustus laughs and throws an upper cut, stopping his fist below Morvant’s chin.

“I tell you what,” Augustus says. “When it comes to fighting? That’s all I need to see. Cause when we’re close together like this? That’s where the fighting happens. I can’t see that well out of this left eye. Like right now, I’m seeing two of you.”

“And your hearing too,” Morvant says,

“Yeah, let me ask you,” Augustus says. “How can I make the ringing stop in this ear,” he asks me, pointing to his right ear. “It’s like I hear the gunshot all the time. But it goes on forever. It’s like baaaaaaaaaaaaaaang!”

We finish our dinner and pay the check. Soon, we head to our respective cars. Augustus doesn’t want his rack of ribs, but he does want a Sprite to go. He holds the door open for everyone. I’m the last person to leave.

“Age before beauty,” he says, which brings a smile to my face.

As we are walking in the darkness of night on the uneven sidewalk outside of the restaurant, Augustus’ gait slows to a toddler’s waddle.

“I’ve fought all around the world,” he says. “But this here? With my vision and my balance? This here is an adventure.”

I feel my eyes welling up. To see this man who was The Drunken Master, one of the best balanced boxers ever to live, a man who could control every limb of his body with precision like a kung fu master, struggling to navigate a sloped sidewalk, not because of the hundred of rounds he fought in the ring for money, and the thousands more he fought in the heat of the gym for fun, but because of one shot, a shot he never saw coming, from an opponent he didn’t get to choose, it was too much of a burden for one man to bear.

How can I make the ringing stop in this ear,” he asks me, pointing to his right ear. “It’s like I hear the gunshot all the time. But it goes on forever. It’s like baaaaaaaaaaaaaaang!”

The next morning, we all get together and head out to breakfast—Augustus, his fiancée Dot, LJ Morvant, James Georgetown, and Georgetown’s wife, Shon, who is known around these parts as “Mama” for the way she nurtures and looks after everyone.

After sitting down at the restaurant, we begin to talk about some of Augustus’ more memorable fights. Unfortunately, many of the endings are not happy ones. Augustus begins to speak louder and become more animated. When his mind is inside the ring, he is happy. His long-term memory about his fights is still very good.

“I used to bust GT’s ass in the gym!” Augustus says,

“Shut up,” Georgetown replies.

The laughter gets louder. Dot and Mama remind the men that we’re in a public place, and we have to keep our voices down.

“Why!” Augustus says. “Girls talk loud all the time!”

Mama teasingly puts her belt on the table and says that if Emanuel doesn’t behave, she’s going to whoop him.

Suddenly, Augustus puts his hand over his eyes, and he begins to slowly sob. Dot takes him outside for a breather. Mama goes with them.

“What just happened?” I ask.

“The belt,” Georgetown says,

“It must have triggered some bad memory,” Morvant says. “We never really talked about it much, but he had a tough time growing up. Sometimes, you never know what memory he can call up or when.”

“I don’t know if he wants to share this,” Georgetown says, “but we would talk in those hotel rooms late at night on the road. Some of the things he would tell me about them homes that he was in? No one should have to go through that.”

Shon "Mama" Georgetown and Dot Anthony console Augustus when he gets upset.

The talk at the table moves back to the indignities Augustus suffered as a fighter.

“Some of the things they did to him just weren’t right,” Georgetown says. “He had one fight in Texas where he was ahead on the cards, he spun out of a clinch, and the referee disqualified him. No warning, no point deduction, nothing! They were protecting their guy! What was his name?”

“Tomas Barrientes!” Morvant says. “Of course, the worst one was Courtney Burton.”

I remember the Burton fight well. It was another Friday Night Fight on ESPN in 2004. Burton was a contender from Michigan. Augustus took the fight on a few days notice in Burton’s home state, and he was dominant.

When Augustus landed a clean body shot that knocked Burton down in the fourth round, referee Dan Kelley called it a low blow and gave Burton time to recover. In the sixth round, Kelley warned Augustus that he would take a point away after a second body punch landed clearly above the belt. In the eighth round, Burton hit Augustus twice to the back of the head, one of the worst fouls a boxer can commit. After it happened, rather than warning Burton, Kelley warned Augustus to keep his head up.

The final injustice occurred in the ninth round. Augustus spun his way out of a clinch, just like a Tekken character, and Kelley deducted a point from Augustus. When ESPN announcer Joe Tessitore asked Kelley why a point was taken away, Kelley screamed at Tessitore for challenging his ruling and said the point was deducted because Augustus turned his back on his opponent, something that doesn’t appear anywhere in the rules of boxing.

When it was over, Burton had won a majority decision, with one judge awarding the fight 99-90 in Burton’s favor. The fight incensed so many long time boxing writers that they flooded the state athletic commission with calls asking to investigate, but nothing ever came of it. It never does.

“You can look at Emanuel’s record. The list of guys he beat, but he still didn’t get the decision: Bill Coddington. Pete Taliaferro, Ivan Robinson. Stephen Smith was a guy Emanuel knocked down with another body shot that they called a low blow, and they disqualified Emanuel because Smith said he couldn’t continue. Of course, Smith was 15-0 at the time.” The list goes on and on.

“We’ve talked about the bad decisions,” Morvant says, “but there were a few guys that Emanuel sent into retirement. Alex Trujillo was a top contender on his way to title shot. Emanuel embarrassed him on ESPN. He only had one fight after that before he retired. David Toledo was a guy who was 25-1. Emanuel knocked him out. Most guys get bums to fight at the beginning of their careers. They pad their records with easy knockouts. He was thrown in there in six, eight, 10-round fights against guys who were world-class fighters. He fought Jesus Chavez in one of his first fights. Chavez would become a world champion! Emanuel just never had anyone looking out for him as a matchmaker. He didn’t have anyone helping him make decisions in his best interest. And he would fight anybody. It didn’t matter to him. He wanted to fight champions.”

But what was it that made Augustus get the short end of the decisions he should have won? Was it all politics or did his Drunken Master showboating style work against him with the judges?

“He knew it did,” Georgetown says. “But he did it anyway. It wasn’t like we didn’t tell him what he needed to do. Wasn’t like he didn’t know what he needed to do. He had to do it his way. Always.”

“That’s who Emanuel was,” Morvant says. “You couldn’t ask Ali to fight like Tyson or Tyson to fight like Ali. Emanuel had to be himself in the ring. The showboating, that’s who he was! He always did things his way. But don’t get me wrong. There were several times throughout his career that Emanuel shot himself in the foot.”

That was never more apparent than Augustus’ fight against Allen Vester. Fighting Vester in his home country of Denmark for the IBF Inter Continental super lightweight title, Augustus felt the deck was already stacked against him.

“I remember him telling me after the fight, ‘These gloves are like pillows,’” Morvant says. “He truly believed the fix was in that night. Unless he knocked out Vester, he truly believed they weren’t going to let him leave a winner.”

With the crowd relentlessly chanting for Vester, Augustus pummeled him for twelve rounds with those two pillows. Despite the gloves, Vester’s face showed the beating. Even though he was winning on the scorecards, in Augustus’ mind, he believed he wasn’t going to get a favorable decision. And he was done getting robbed. So he decided he was going to rob them first. Toward the end of the twelfth and final round, Vester began raising his hands in victory, as though it were predetermined.

When Augustus realized that he couldn’t knock Vester out, with less than ten seconds in the fight, he let Vester land a meaningless pitter-patter combination to his face. Augustus fell backwards to the canvas as though he were falling into his bed from exhaustion. He spread out his arms and legs like a starfish, waited for the referee to count to ten, then quickly jumped back up, raised Vester’s hand, and exhorted the crowd to cheer for Vester. On the telecast, you can clearly hear Augustus’ distraught trainer yell at him in a southern accent, “But you let him won!” Augustus just shrugged his shoulders. The boxing world thought the fight was fixed. Morvant provides a different view.

“You’ve met Emanuel now,” he says. “So you know, money didn’t mean anything to him. And he was way too damned competitive to lose a fight on purpose. But he honestly thought he was going to get screwed again, so he wanted to screw them first. He felt if he wasn’t going to get the decision, he was really going to draw attention to it. He wouldn’t give them the satisfaction of going to the cards and screwing him. He told me after the fight, ‘They’re going to through him to the wolves, now,’ meaning Vester. And that’s exactly what they did. Vester got destroyed by Zab Judah after that.”

Floyd Mayweather—one of boxing’s all-time greats who has been in the ring with champions such as Oscar De La Hoya, Shane Moseley, Miguel Cotto and Manny Pacquiao—still refers to Augustus as the toughest fighter he’s ever faced.

Dot accompanies Augustus back to the breakfast table.

“I’m sorry about that,” he says.

“Sorry about what?” I ask.

“My brain is messed up,” he says. “Sometimes things don’t make sense. I’m still trying to figure things out. Why are you doing this story again?”

“Because boxing fans still care about you and want to know how you are doing.”

“Well, I’m sorry I don’t have a fight to promote. But I guess this is the biggest fight I’ll ever have, right?”

We finish breakfast and head to Georgetown’s gym, where he trains some younger fighters in the area. Emanuel starts to playfully hit the speed bag.

“Look at him, Dot!” Mama says marveling. “Look at him go! He’s just full of surprises!”

After a while, Augustus’ sight begins to betray him. He starts to miss the bag.

“Shit!” he yells in frustration and walks away.

But a minute later, he’s pounding away on the heavy bag, horsing around with Georgetown and Morvant, just like old times.

“Do you think this has been good for him?” I ask Dot. “I didn’t realize that he hadn’t been to the gym, and he’s been a lot more physically active since we’ve been here than he’s been.

“Oh, this is very good for him!” Dot says. “Just you folks being here, caring about him has been good for him. Look at him! He’s full of life! People need to know his story, and people need to know how far he’s come back from where he was. Emanuel gave his life to boxing. All those places he fought on a few days notice. What has boxing given him? Where are all those people now? He can’t even afford to go to the doctor to get the help he needs.”

Emanuel gave his life to boxing. All those places he fought on a few days notice. What has boxing given him? Where are all those people now? He can’t even afford to go to the doctor to get the help he needs.

When it appears that he’s exerting himself too much, Dot pulls him aside and slows him down. She clearly cares deeply for him. All of his friends do as well. As unlucky as Emanuel has been in his life, you can feel the love that now surrounds him.

When we leave the gym, I ask Emanuel and Dot if they will take a photo with me. We put out arms around one another. As our photographer begins to take the photo, Augustus raises his right middle finger to the camera. I then raise mine as well.

“Emanuel!” Mama yells. “You’re corrupting him!” Everyone laughs. Emanuel laughs the hardest. The Drunken Master always does things his own way.