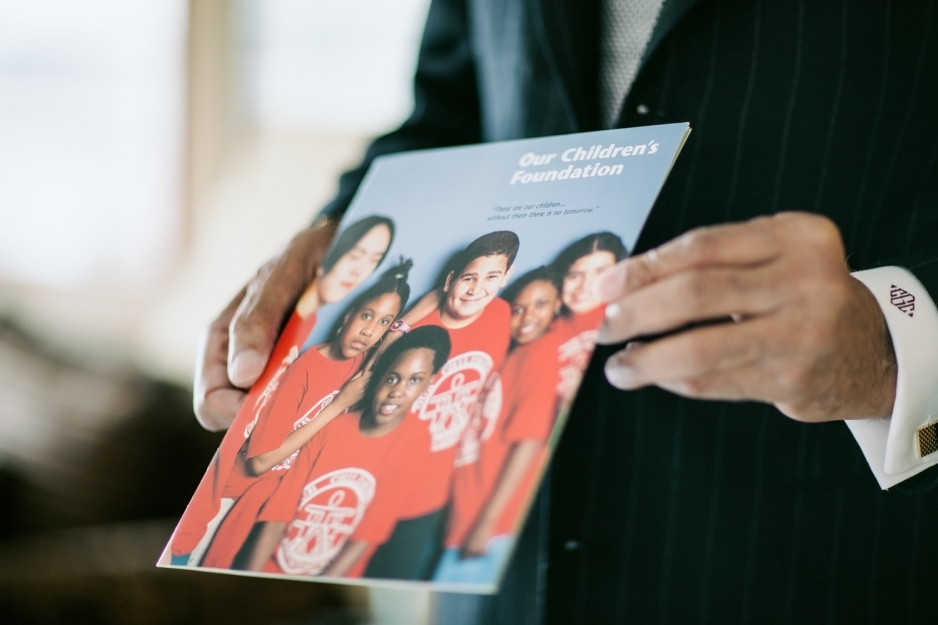

In the basement of the Eastern Baptist Church in New York City, several former basketball stars are leading a clinic for underprivileged kids. Hall of Famer and New York basketball legend, Nate “Tiny” Archibald, leads the kids through drills. Former NBA players, Sam Vincent, Hollis Copeland and Tom Hoover instruct the students on the fundamentals—keeping your dribble low and your head high. And seated next to the court, watching the proceedings from a short distance, is an impeccably-dressed tall white-haired gentleman. “You should talk to him,” Hoover says to me between drills. “If you want to talk about basketball in New York, that’s The Godfather!”

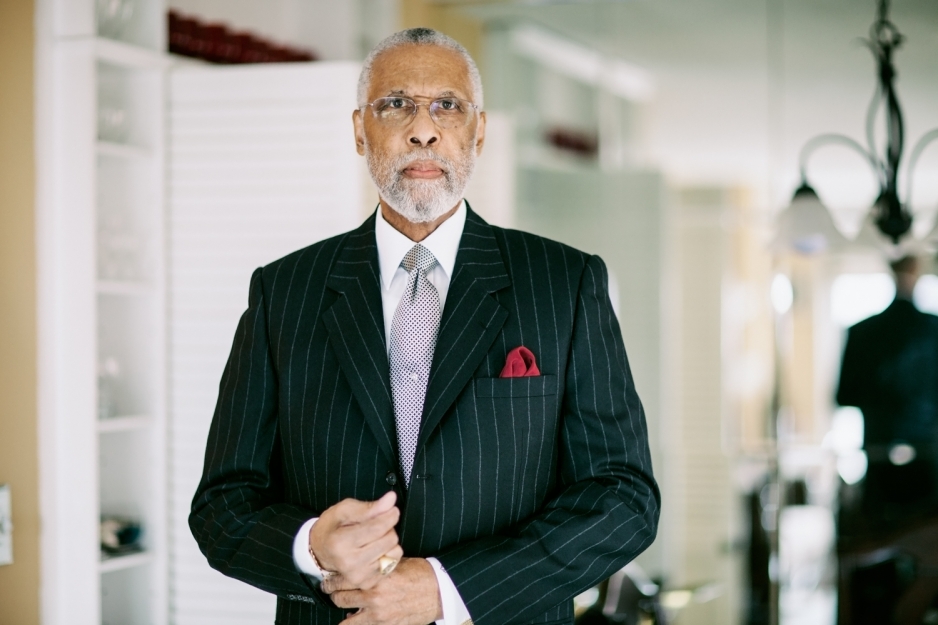

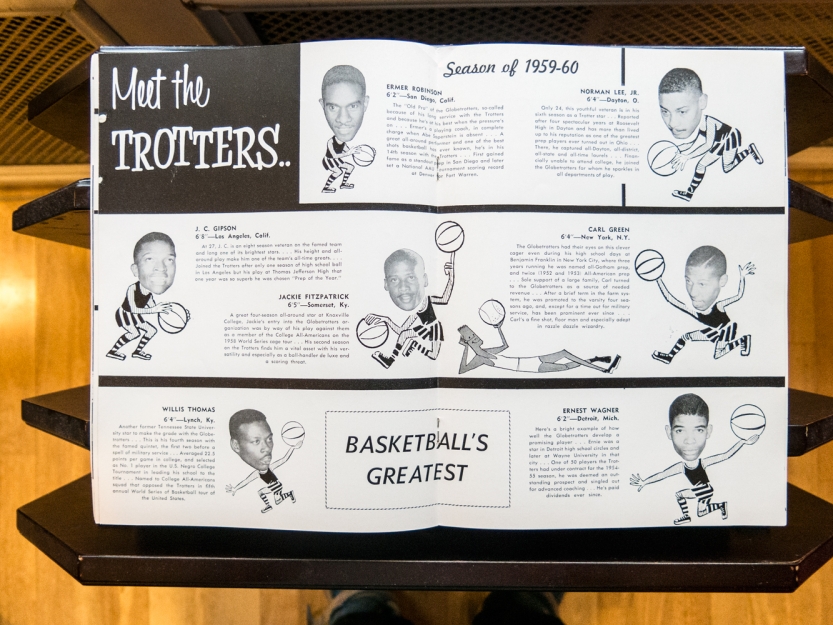

Upon introducing myself, I learn that the gentleman’s name is Carl Green. Green is a soft-spoken 79-year-old man who will not speak about his basketball career unless you ask. During the 1950s, he played for the Harlem Globetrotters. On the rare occasion when the 6-foot-6 Green shares this information, people usually ask if he was the guy who threw the confetti bucket. But take one look at the dignified Green and you will know for yourself very quickly that he was never anyone’s clown. What I was to receive from Green that day, and in the following weeks was not a greatest hits of Globetrotter comic sketches. Instead, it was a masters degree in basketball history, civil rights, and the plight of the African American athlete in the 1950s.

For an African-American teenager growing up in the 1950s, there was no bigger dream than wanting to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers or the Harlem Globetrotters. The Dodgers story has been told many times—the beloved team of Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe. It was the team that broke baseball’s color barrier and went on to National League dominance.

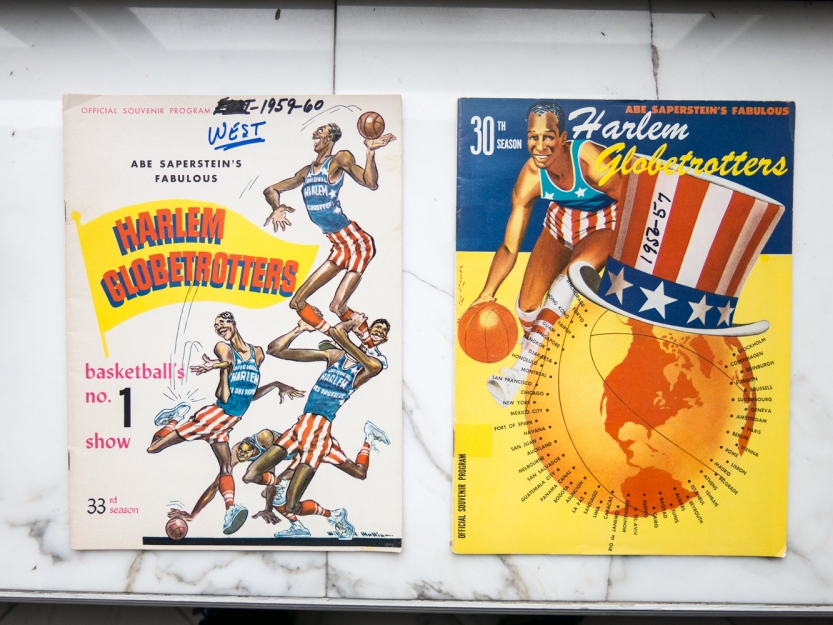

But the story of the pre-1960s Harlem Globetrotters has been papered over by the images we’ve seen too often— players in red, white and blue uniforms pulling down the pants of dimwitted referees or hiding basketballs in their jerseys from hapless opponents. Though the new generation of Globetrotters has entertained millions of children throughout the world, the pre-60s Globetrotters were so much more than entertainers. They were color-barrier pioneers of a soon-to-be global game.

As a teenager growing up in Harlem, Green could only see the team named after his own Harlem neighborhood in movie theater highlights. There were no televised games at the time. And the Harlem Globetrotters wouldn’t even play a “home game” in Harlem until 1968. Truth be told, the Harlem Globetrotters were created in Chicago in the 1920’s by an enterprising businessman named Abe Saperstein. Believing that Harlem was the capital of African-American culture and cachet, Saperstein gave his team the Harlem moniker.

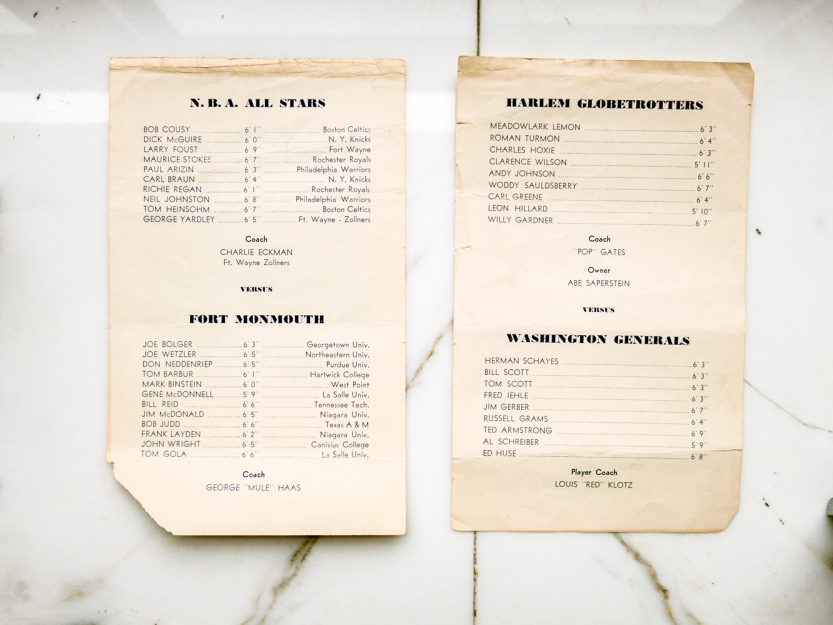

As with most young boys, Green was well aware of the Globetrotters exploits. Before the NBA became integrated, the Trotters were the African-American team that took on and defeated Hall of Famer George Mikan and the reigning “World Champion” Minneapolis Lakers.

To the Harlem community, the Globetrotters were a natural extension of the great African-American teams that most people outside of New York never got a chance to see. The most famous team of that group was the Harlem Rens, led by Hall of Fame player, Harold “Pop” Gates.

Green and best friend Jack DeFares were attending Benjamin Franklin High School in New York City—Pop Gates’ alma mater. Because of their outstanding play, Green and DeFares were the only two African-American players named to New York’s highly competitive All-City team.

As Green and DeFares began to receive attention, Gates took the two young men under his wing. “Pop and the other guys on the Rens looked out for us,” Green says. “They were big names in the basketball world. They wanted to help us not just in basketball, but in life. They would show us, ‘This is how you get a job at the police department. At the post office. At the sanitation department.’ They had connections in all of these places. Black people weren’t getting jobs in places like this at the time.”

Gates offered young Green and DeFares two options—he could help get them scholarships at Michigan State, or they could join the Globetrotters. Unbeknownst to Gates, Green had also received a scholarship offer to Seton Hall University. “They wanted me to play there,” Green says, “but they wouldn’t take Jack. They said he had low grades. I didn’t have any grades. I didn’t spend a single day in a classroom in high school. But they were willing to take me. Can you imagine that? But if they weren’t taking Jack, they weren’t getting me.”

While they were mulling the offer over, an enterprising young college coach paid Green and DeFares a visit. He told them his name was Clarence Gaines, and he was the head coach of Winston-Salem State University. “I didn’t even know where North Carolina was,” Green says. “I had never left New York before. But Gaines really wanted us to come there and play for him. Jack and I asked him if we would take a few of our friends as well, and he said he would. I also asked for a tutor, because I didn’t think I could handle the work, and he said no problem. So we went to Winston-Salem together.”

DeFares and Green became instant stars at Winston-Salem State, putting the program on the basketball map, and eventually putting Gaines in the Basketball Hall of Fame. But Green, who hadn’t received any education in high school, never received the tutoring he needed to make a go of it in college. When he decided the university couldn’t fulfill the promises made to him, he left to join Pop Gates and the Globetrotters.

Once Green got to the Globetrotters, he met his first roommate who had also just joined the team, a young kid from Wilmington, NC named Meadowlark Lemon. “Meadowlark was being groomed to become a showman,” Green says. “That was the guy who stood in the pivot and did the routines. But I was there to play basketball.”

For $450 a month, Green and his teammates would play six times a week and twice on Sundays. “Abe Saperstein put together a team of College All-Stars that we would play all over the country,” Green says. “They were the best college players at the time. We would find out that Abe was paying those guys more than he was paying us.” The College All-Star teams were made up of All-American players that would attract crowds in whichever region they would play due to their local popularity. Many of the players on those teams would end up playing in the NBA. Some, such as Tommy Heinsohn and Bob Cousy, would go on to the Hall of Fame.

NBA teams desperate to draw crowds would book the games as part of a doubleheader to help sell tickets. “The play in the NBA was terrible at the time,” Green recalls. “It was a lot of big slow guys who liked to fight. Teams would hold the ball and guys would just beat on each other. It was a completely different game than it is today.”

Fans were intrigued by the fast paced, fast break style of the Harlem Globetrotters. “The Rens started that style,” Green says. “Red Auerbach saw the Rens play and he took all of that fast break stuff to the Celtics. We added our own flourish to it with some dunks.”

In some cases, when the team was playing a lesser opponent and the score began to get out of hand, the comedy routines evolved to keep fans interested. The humor injected in between moments of a new style of fast-paced basketball made the Globetrotters must-see entertainment.

But after the Globetrotters played the first game of a doubleheader, fans would exit the arena, leaving the fledgling NBA teams in towns like Syracuse and Fort Wayne to play in front of empty seats. “Once the owners started to see that, they flipped the games,” Green says. “They would make the NBA guys play first, and then we would go on second and close the show.”

The Trotters became so successful that Saperstein set up three teams— one team of young players to play out West and learn the routines, one team in the South, and his main team of stars in the Northeast, who would play the big arenas.

Once, when Green complained about money, he got shipped off the Eastern club to play on the Western team. “That was Abe’s way of keeping me quiet,” Green remembers. “He was putting me in my place. But I wasn’t the kind of guy who stayed quiet if I saw something that wasn’t right.”

Green found a kindred spirit on the team in a rookie who also wasn’t shy about expressing his opinions. His name was Bob Gibson. Gibson also got sent to the Western team to be Green’s roommate. He would eventually go on to become one of the greatest pitchers of all time.

“Gibson was a great player,” Green says. “A great athlete. He could have been a great basketball player if he wanted to follow that road.” In Gibson’s autobiography, Stranger to the Game, he would recall playing against the Globetrotters for the College All-Stars, essentially as a tryout to join Saperstein’s team.

After driving past Green’s teammate Andy Johnson, Gibson was greeted the next time down the floor by Johnson’s elbow, which sent him tumbling to the ground. “This is my territory,” Gibson recalls Johnson saying. “Come in here again and it’s your ass.” Gibson writes, “His remarks turned out to be the best pitching advice I ever received. Eventually, I came to regard the outside corner of home plate the same way that Andy Johnson felt about the lane.”

After a grueling travel schedule throughout the winter, Saperstein would select a number of the players to head up a European Tour during the “summer offseason.” The European tour would take Green and his teammates to 15 countries and 62 cities.

The Trotters would play 99 games in 101 days in places where Americans weren’t exactly the most welcome guests. “Abe had contacts everywhere,” Green says. “He knew people in the military. He knew people everywhere. Wherever we went, he would go on to the next city to lay the groundwork.

Places like East Germany, Russia, and Yugoslavia were off-limits to Americans during the Cold War. But not to Green and the Globetrotters. “I remember driving to East Germany after the war,” Green says. “We were driving through all these checkpoints. I told Andy Johnson, ‘What if they decide to keep us here?’ We were a little scared, but we pretended not to be.”

In another country, Green and his teammates came back to their hotel rooms to find that their luggage had been searched and film confiscated from their cameras. “They had guys following us everywhere,” Green remembers. “One time, Andy saw some guys following us, so he just ran. I started running with him!” Green remembers laughing now. “We saw the world in a way no one else could have. Not even if you were in the military.”

Despite the sometimes cloak-and-dagger conditions, the Globetrotters would lay down a battered old basketball floor and entertain thousands of strangers, some of whom were seeing basketball for the first time. “You wouldn’t believe some of the places the Trotters played,” Green says. “Once they had to put all of these office desks together to make a stage so everyone could see. Then they put the court together on top of it. Another time, the team played in the bottom of an empty swimming pool.” In many cases, the court the Globetrotters brought was the only basketball court in the city. In many cases, they were the first pro basketball team, and in some cases, the first black athletes, that a country would ever see.

The tours were highly successful and profitable for Saperstein. The money made was estimated in the millions. But the players weren’t so fortunate. The only player for whom money was no object for the Globetrotters was a young man out of Kansas University named Wilt Chamberlain. Chamberlain joined the team for what would have been his senior year at Kansas. He loved playing with the Globetrotters so much, he would often go back during summers as a pro to play with the team. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between Chamberlain and Green. The two friends would even invest in the real estate business together.

Though Wilt was being paid handsomely for being basketball’s greatest gate attraction, the other players received as little as Saperstein could get away with paying them. Just a few years earlier, Saperstein had seen his two biggest name players, Goose Tatum and Marques Haynes, leave the Globetrotters over money to start competing teams. He was determined not to promote the other players to much and make the same mistake.

Despite the fame and the ability to see the world that the Globetrotters brought him, Green quit the team. “It was time to start making a living,” he said. “Some guys enjoyed the fame and didn’t want it to end. They wanted to go to clubs and meet girls and all that. I was never much for that. I was sending the money home to my mother to hold for me. For me, it was about what was right. We played so many games, made so much money for people. They used our pictures in ads for things and we never saw a dime. When I went on the European tour, they paid us less, even though we played more games and had more expenses. I had enough.”

“When I got back to Harlem, I told people about some of the things I had seen before,” Green continues. “Germany was bombed out after the war. In some countries, I saw people with no arms begging in the street for money, just so they could eat. I told people, ‘If you think you have it bad, you should see what I’ve seen.’”

Still at the peak of his basketball ability, Green would go to tryouts with the Philadelphia Warriors, where his best friend Wilt Chamberlain was now a big star. But unable to get a decent contract offer, he left and went home. “It has always bothered me that people thought I got cut from the team,” Green says. “They wanted me to play guard, which was a way for them to try to pay me $5,000, when I would have made $10,000 as a forward. So I left. Wilt tried to talk me out of leaving, but I had had it. I needed to make my own way.”

Before the Boston Celtics championship teams changed the landscape, NBA teams wouldn’t carry more than three African-American players on their roster. The abundance of young talent made it even more difficult to get a decent-paying job in the NBA and kept the Globetrotters flush with young low-paid talent. With the deck stacked against him, Green wanted more control over his own destiny.

When he came back to New York, Green got a job bundling boxes. A basketball fan recognized him and got him a better job in the Garment District making $200 a week, twice as much as he would have made in the NBA. On weekends, Green would supplement his income by travelling throughout the Northeast to play in the Eastern League for $50 per game. “At that time, there were teams in the Eastern League that could beat NBA teams easily,” Green says. With only 8 NBA teams, if the Eastern League existed today, every team would be the equivalent of a playoff team.

After a distinguished 9-year career in the Eastern League, Green kept a connection to the game by coaching teams in the storied Rucker League in Harlem, leading teams to four straight championships. He would go on to coach and mentor Happy Hairston, Archie Clark, Emmette Bryant, Freddie Crawford, Tom Hoover, Willis Reed, Pee Wee Kirkland, Walt Frazier, Howie Komives, Bud Stallworth.

Green would later invite me to his home to share more stories. As we look at the photographs that line his wall, it’s almost as if you were viewing a diorama of basketball and civil rights in New York City. There is the photo of him and DeFares as the only African-American All-City players in the team picture. There’s a photo of Green as coach of one of the many championship Rucker teams he coached. A large black and white photo shows Green and Chamberlain flanking a young Lew Alcindor and friend at a New York City restaurant. Green and Chamberlain took the young man out to celebrate his high school graduation.

And the most prized photographs in Green’s collection are those of his beautiful bride, Dean, who passed away last year. One striking image shows her at a young age playing golf. When I remark to Green that it’s the first photograph I’ve ever seen of a young black woman playing golf, let alone in the 1950s at a time the sport was not kind to women or African-Americans, he smiles and says, “That’s my wife!” On the far wall, Dean is photographed with every major dignitary you can imagine, from Martin Luther King Jr to George HW Bush. “Dean raised money for a lot of people. Whenever Dr. King came to raise money for the civil rights movement, Dean had a check for him. She helped Bush, Bill Clinton. Everyone knew her.”

And lastly, there are the photos of Green’s former teammates on the Globetrotters. Many of those pre-1960’s Globetrotters teammates are gone now. Only a few still remain, mostly in obscurity. None of the former players receive pensions of any kind, including a few former players who live in dire circumstances. “I don’t need the money,” Green says. “I don’t want for anything. I’m doing just fine. But some guys can use the help. After all the years they put in, all the money they made for other people, to not give them what they deserve, it’s not right.”

And if it were ever possible to sum up the life of someone with as rich of a personal history of Carl Green’s, it would be this. He was a great athlete. He is a great mentor. And he always stood up for what was right.