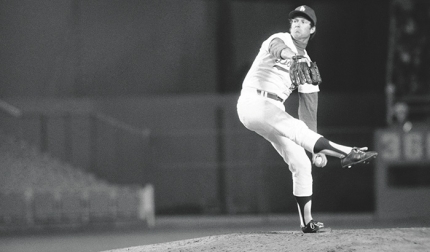

Far too often, the decision for an athlete to retire is made for them. They sit at home waiting for the next team to call and the call never comes. But John Flaherty is an exception. He knew the moment he wanted to retire from Major League Baseball.

“I had received a call from the Boston Red Sox,” Flaherty remembers. “They had a deal on the table for Doug Mirabelli, and they wanted me to join the team to catch Tim Wakefield. They were going to be good, and I was excited about the opportunity. But after being away from my family for two days in Fort Myers, FL for spring training, I didn’t feel it. I didn’t want to work at it anymore.”

Work was something Flaherty never shied away from over a 14-year career behind the plate. Originally drafted by the Red Sox, Flaherty received a $5,000 bonus as a 25th round pick. Leaving George Washington University after his junior year, Flaherty promised his dad that he would go back and finish college as soon as he could. “It was the best thing I ever did,” he says. “I was disappointed to get drafted as late as I did. Baseball was by no means a sure thing for me. ”If not for baseball, Flaherty might have joined his two brothers in law enforcement. “They both still work for the D.E.A.,” Flaherty says. “That easily could have been my career path,”

Working on his game through the minor leagues, Flaherty began to show promise as a catcher that could handle a pitching staff well. “My reputation in the minors was as a guy who could catch and throw but couldn’t hit,” Flaherty remembers. “When I go to the big leagues, I thought I would be a back up for a couple of years, and that would be great. Then I got traded to the Detroit Tigers. (former Major Leaguer) Larry Parrish changed my swing, changed my mindset offensively, and all of a sudden, I learned how to hit at age 27 and got a chance to play every day in Detroit.

Flaherty continued to make the most of his opportunities—first with Detroit, than San Diego, Tampa Bay and later in his career as a reserve catcher for the 2003 New York Yankees team that won the American League pennant. “At that point, my body couldn’t handle playing every day. I knew if I tried to catch every day, my body was going to break down.”

After Flaherty became a free agent, the Red Sox called and he found himself with the dilemma to continue playing or to return home. “It was my wife who actually encouraged me to stay,” Flaherty remembers. “She said, ‘At least stay for the games.’ She felt once my competitiveness kicked in, maybe I would change my mind,” Flaherty got behind the plate for a few preseason games, including one with the knuckleballing Wakefield. “It was a disaster,” he says laughing. “Balls were flying all over the place. I knew I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t want to learn to do it. I played too long. It’s time for someone else.”

Flaherty went in to then-manager Terry Francona’s office to tell him it was time to say goodbye to the game. But it wasn’t so easy. The next day, there were several messages on Flaherty’s phone, asking if he would be interested in broadcasting. “I’m not sure how they knew,” he says. “Maybe they saw me on camera later in my career. Maybe some people put in a good word for me.”

After a few auditions, the Yankees found a spot in their rotation on the YES Network, where Flaherty has become a fixture for fans who love the inside baseball of calling pitches and trying to set hitters up. “It’s been a perfect job for me,” he says. “You have such a knowledgeable fan base here in New York, when you are calling a big game, the adrenaline rush is still there.”

Flaherty began his apprenticeship in the booth with some fellow Major League alumni with a great deal of experience, including Ken Singleton, Jim Kaat and the late, great Bobby Murcer. “When I broke in,” he says, “Jim Kaat gave me the best advice. He said, ‘We’re just watching the game, having a beer in the bar and talking to our friends.’ I put in a lot of preparation but once the game starts, I try to be as casual as possible. If the game situation dictates it, the information will come naturally.”

There are days when Flaherty misses the adrenaline rush of chasing another pennant. Perhaps when his daughter and two sons leave for college, he may consider a return to the dugout potentially as a manager, if the timing is right. Until then, he’ll enjoy calling every pitch from the announcer’s booth. “Calling the pitches is something you can’t turn off as a catcher,” he says. “I’ll probably be doing it for the rest of my life.”